DUNWICH AS BEAUTIFUL NIGHTMARE

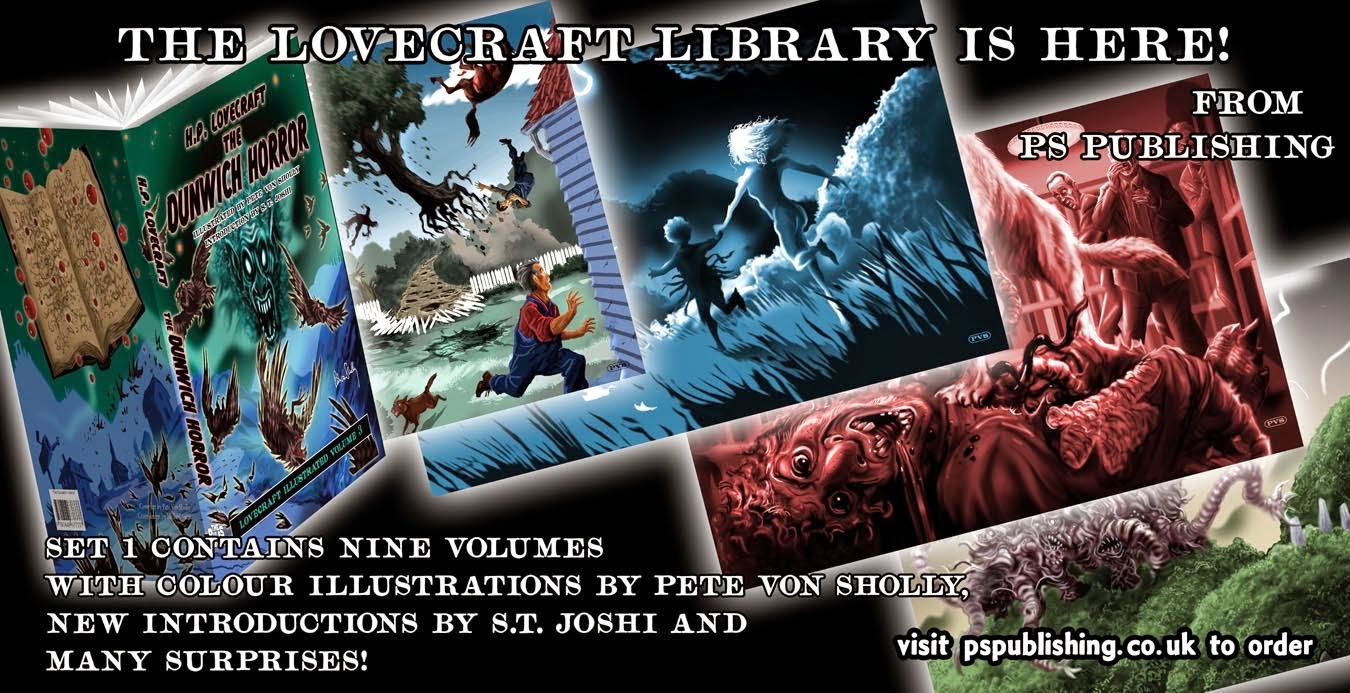

One of ye wonderful things to happen this year was Pete Von Sholly's invitation for me to write wee essays for the Lovecraft Library series from PS Publishing in England. I've written new essays for five of the initial nine volumes. Through some mishap, my original essay for THE DUNWICH HORROR volume wasn't used (it was intended to replace an old fanzine article that was included in the book). I cannot now remember if I've publish'd my new essay here, so I thought I wou'd do so nigh. I have an itch to write essays on Lovecraft's fiction especially for this blog, to share my ideas about the work and my passion for it. (For instance, I just noticed the very peculiar tense in which Lovecraft wrote "The Terrible Old Man," and I have no clue what to call the tense chosen by HPL. If I remember, I will ask S. T. at his Memorial Day Cook-Out this week-end.) So, here is my unpublish'd essay on "The Dunwich Horror." I do not mean to pose as any kind of scholar, for I am not. These are but ye ramblings of a fan.

DUNWICH AS BEAUTIFUL NIGHTMARE

W. H. Pugmire, Esq.

There is one beautiful illustration in this volume of PS Publishing's Lovecraft Library that perfectly captures one magick moment in this story: "Considerable talk was started when Silas Bishop--of the undecayed Bishops--mentioned having seen the boy running sturdily up that hill ahead of his mother..." Pete's illustration for the scene in this volume is perfect in tone and helps to illustrate one of the story's powerful features--its sense of place. Lovecraft doesn't simply make up a town called Dunwich--he conjures a mythical setting that magnificently enhances the sinister atmosphere of the tale, atmosphere that was all-important to this outstanding literary artist. The potent opening paragraphs of the story set the mood superbly, with poetic language and spectral imagery; and then, at the end of the third paragraph, Lovecraft gives us one of his finest and perfect sentences: "Afterward one sometimes learns that one has been through Dunwich."

Why was it essential to Lovecraft to create his mythical towns of Dunwich, Arkham and Kingsport? I do not know if he ever articulated his reasoning for these creations, but I think, in part, it was in order to give him complete artistic and creative control as far as atmosphere is concerned. These are places touched by the Outside, intimately so; and those unfortunate souls who dwell within these spectral pockets of unearthly horror are tainted absolutely, and aware of their contagion. This aspect of Lovecraft's art affected me greatly when I began to write my own tales of Sesqua Valley, although I gave it my own wee twist and have nameless contamination a source of eldritch celebration, a thing more desired than feared.

S. T. Joshi has been severely critical of "The Dunwich Horror," to the point of suggesting that it is one of Lovecraft's artistic failures. This is nonsense. In I Am Providence (page 719), S. T. states: "In an important sense, indeed, 'The Dunwich Horror' itself turns out to be not much more than a pastiche," and then goes on to list the other works from which Lovecraft got his ideas for the tale. Rather, Lovecraft has taken his many influences of theme and plot and, with his expert artistry, created a story that is uniquely his own in every way. One of the story's powerful components is its use of character. The criticism aimed at Lovecraft that he was incapable of creating interesting or realistic characters is idiotic, and his use of character is one of the points of perfection in his weird fiction. The portrayals found in "The Dunwich Horror" are remarkably effective and exactly right for the part they play, with each a faultless portrait. Most fascinating, for me, is the bizarre and tragic figure of Lavinia Whateley. She is deftly painted, and yet her story has untold depths, and a clever writer could construct an entire novel from the hints that Lovecraft has given us. (Indeed, our genre's finest modern poet, Ann K. Schwader, has written an entire sonnet sequence concerning the doomed Lavinia.) Miss Whateley is a symbol of all that is fabulous and awful in Dunwich. She is an innocent who was, perhaps, ravaged by her father when he was possessed by the force known as Yog-Sothoth. She loved Wilbur absolutely, and was perhaps murdered by him. She was the unsophisticated, unworldly child who became corrupted by books she studied with her insane sire.

This is a story of supernatural horror. Some have claimed that Lovecraft's monsters are "merely" aliens from outer space, and they are wrong. Yog-Sothoth is not a monster that has filtered to earth through cosmic realms but rather a completely supernatural daemon conjured forth by black magick. What kind of "alien" can be summoned by the arcane language of a nameless grimoire? This magnificent monster comes not from ye cosmic abyss but from alternative dimension--the Outside. It is, in every way, not of this world. It does not belong in any sane universe, and it is impossible to comprehend its nature. Yog-Sothoth is as perfect a symbol of the unearthly as the stigmatic fiend featured in "The Colour out of Space," which is indeed, as the story's title instructs us, cosmic. We never encounter this daemon in the story, yet feel its presence and influence enormously.

The portrait of the "Dunwich Horror" itself, although effective in its way, is the story's weakest point. It is a wonderful effect of plotting, to center the focus of the first portion of the story on Wilbur, and then to concentrate completely on the monstrous twin and its destructive nature. Robert Bloch performed a similar feat in Psycho, and Wilbur's death may be thought of, playfully, as the shower scene in "The Dunwich Horror." Alas, the climax is simply silly, and although it thrilled me when I was very young, it now makes me groan. The image of a bloke wielding an insecticide spray-gun filled with hoodoo powder which is then shot at the invisible titan so as to give it a shape that can be described is inept. Lovecraft perhaps thought it would be effective to have the scene described by yokels who watch from a distance, but here he erred. It would have been far more effective for the scene to have taken place among the three courageous men, on the haunted hill, directly in the close-at-hand presence of the beast, and described from their unimaginable proximity to this madness out of time. Still, we have that delicious moment of hideous revelation, where it is shewn that half of the horror's face resembles that of its proxy sire, Wizard Whateley. The hints and suggestions there implied are a Dunwich horror indeed!

You make some valid points with your criticism.

ReplyDeleteI feel that perhaps the culture of the times lead to some naivety on his part (pulps included). His work was a whole new genre after all, and I sense he did take the easy path on some of his work; still, I'm so glad he wrote so many engaging stories!